This piece is cross-posted from my Medium account. Check it out for more posts like these.

Japanese corporations have long been emblematic of meticulous craftsmanship, unwavering dedication to quality, and a distinctive commitment to tradition.

Yet, for decades, they were equally known for their marked aversion to change, being deemed as monolithic entities steeped in tradition, exhibiting a level of conservatism that appeared to stall innovation and shareholder returns. This once-prevalent perception painted a picture of inefficiency, caution, and a lagging pace in the global economic race.

Since peaking in December 1989, the Nikkei 225 has yet to recover.

But this is changing.

Recent years have seen sweeping corporate governance reforms, a reinvigorated focus on shareholder value, and an ardent embrace of progressive business strategies.

Japan is back in vogue.

History

Since the Nikkei bubble burst in 1989, Japanese corporations have become increasingly conservative and inefficient. Most significantly, they began hoarding cash.

They did this for several reasons.

First, because of their prior experiences of previous economic crises (e.g. 2008, 1997). In these crises, financial institutions, who were greatly influenced by the Bank of Japan’s policy stance, tightened their lending measures toward companies. These austerity measures resulted in companies not obtaining sufficient cash management support from financial institutions.

As a result, a corporate mindset took hold that during an economic crisis, relying on loans from financial institutions and policy support from the Bank of Japan would be unfeasible. Corporate attitudes began shifting toward accumulating their own savings to rely on during future crises.

Hence, during expansionary economic periods, businesses began accumulating their own savings to rely on during future crises. They curbed their spending and borrowing, while also retaining more earnings to build up a substantial cash reserve.

The following chart from JRI Research Journal shows how conservative Japanese companies have become, significantly reducing their debt positions:

Second, low growth expectations for Japan’s economy has further increased companies’ conservatism. Due to unfavourable demographic decline trends and low GDP growth rates, companies have begun to adopt generally low growth expectations for the future. Due to these lower expectations, companies are less likely to invest back into their businesses and instead further accumulate cash. Indeed, according to another chart from JRI Research Journal, lowered expected growth rates have contributed to slower capital investment.

This accumulation of cash means that companies spend less on investments and capital expenditures. Accordingly, they cannot remain as competitive and cannot execute more aggressive growth plans. With cash not being put to efficient use, it simply piles up on the balance sheet and drags down profitability metrics like return on equity (ROE).

This adds up. According to Jefferies, at the end of 2022, MSCI Japan Index had a ROE of 9.9%, while the MSCI World Index had one of 14.7%.

Past measures have been taken to reinvigorate companies. 10 years ago, then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe launched Abenomics, a plan with “three arrows” aimed to revitalise Japan’s sluggish economy. The third arrow, structural reforms, which was partly meant to bring about corporate governance reform to make companies more efficient. However, investor optimism around these reforms has fluctuated. Overall, the consensus is that Abe’s third arrow largely failed. Corporate governance reforms that were implemented did not substantially revitalise public companies.

Recent Initiatives

But recent reforms are much more promising.

First is the 2021 initiative to reform the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE). The TSE was reconsolidated from the previous four sections (First, Second, Mothers and Jasdaq) into three new ones (Prime, Standard and Growth).

For companies to be listed in the most reputable Prime section, regulators required that they maintain a ratio of tradable shares at or above 35% of the outstanding amount. Though similar requirements were implemented previously, there was a loophole due to the uniquely Japanese system of keiretsu.

This practice was defined by cross-shareholdings, where a diverse group of companies, such as banks, manufacturers, insurance companies and more all held stakes in each other. This practice was meant to align the incentives of various companies together to foster a more harmonious business environment.However, it often fostered an uncompetitive and opaque environment, where companies simply stuck to their existing business partners, and were not incentivised to seek out more competitive options, causing less efficient business practices.

To combat this, the TSE redefined tradable shares to exclude shares held by other companies in this cross-shareholding practice. This has incentivised Japanese companies to rethink their capital alliances with business partners, hence promoting more efficient capital allocation and driving long-term shareholder value.

Second, the TSE is also actively tackling companies with low valuations. In march, it reported that 50% of the companies listed on its Prime exchange, and 60% of those listed on the Standard exchange, had ROEs below 8% and price-to-book (PB) ratios of less than one.

The TSE is now requiring these companies to detail plans to directly improve their share price. This includes plans to improve their capital efficiency, as well as actively showing how they are “advertising” themselves to investors, through measures such as publishing their public disclosures in English.

Moreover, should a company fail to achieve improvements in its efficiency and stock valuation, it may be subject to further supervision, as well as risk delisting within six months.

Such measures are unlikely. But due to a strong sense of peer pressure amongst Japanese executives, as some companies pursue corporate governance reform measures, others will tend to follow too.

Success!

So far, these measures have worked.

Japanese companies are increasingly putting their cash to good use. And with aggressive speed, too.

There are two main ways companies can directly return cash to shareholders: stock buybacks and dividends. Both these measures have been increasingly taken by Japanese companies, as illustrated by the following charts from Fidelity.

And these measures are making Japanese firms more efficient. Return on Invested Capital (ROIC), another profitability metric, is skyrocketing:

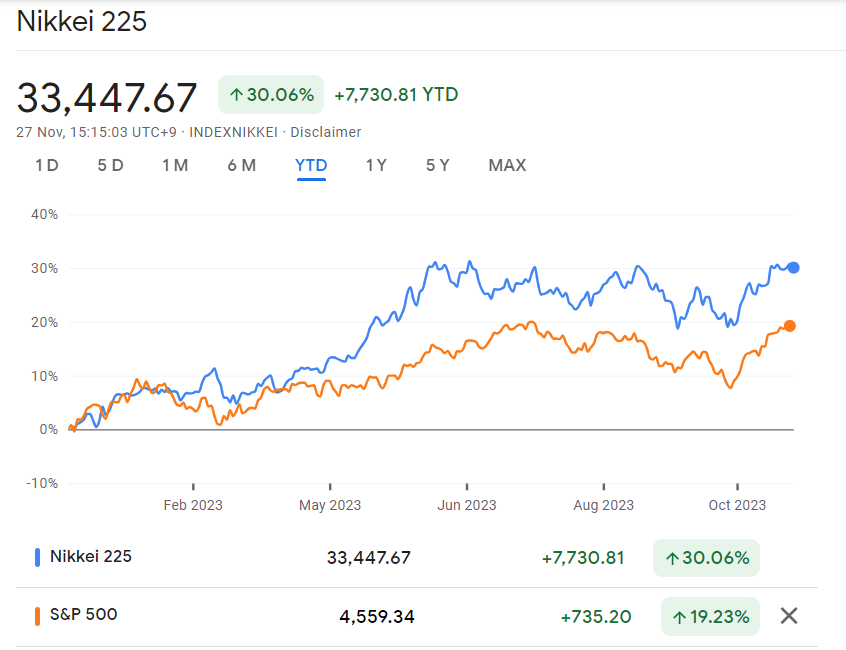

Year to date, the Nikkei 225 is also up significantly, even beating the S&P 500:

Of course, corporate governance reform isn’t entirely responsible for the reinvigorated optimism surrounding Japan. Much of that is attributable to greater business confidence, healthy inflation, and a decently resilient economy.

That being said, Japan is still attracting numerous foreign investors, with massive foreign inflows into Japanese equity.

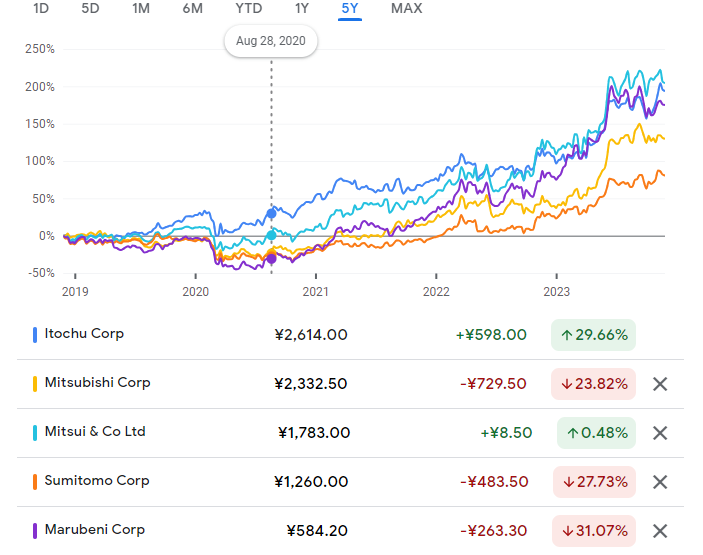

Most notably, famed investor Warren Buffett increased his stake in five Japanese trading firms to 7.4% earlier this year, after his original purchase in August 2020.

And these investments have been extremely successful since:

Conclusion

Overall, Japanese firms’ prospects look bright. Apart from the efficiency-seeking reforms I’ve covered so far, there are also numerous other initiatives aiming to make Japanese firms more competitive.The business landscape has experienced increased female representation on the board, a more suitable environment for activist investor campaigns, and a renewed focus on catching up in the digital age.

Of course, there are risks that these changes may fizzle out, as they have done in the past. For example, the introduction of Abenomics and its initial corporate reforms led to bullish periods, before eventually petering out.

It also remains to be seen if Japanese firms would take the harsh steps necessary to truly drive long-term efficiency. So far, Japanese firms have been relatively willing to cut back on cash reserves to implement more aggressive share buybacks and dividends policies. But to truly drive long term efficiency, Japanese firms will need to curb their conglomerate tendencies and cut underperforming business units. Some companies, like Hitachi, are doing so actively. But it is too early to say that this attitude has turned mainstream.

Still, it’s clear that structural reform has been set in motion.

Leave a comment