This piece is cross-posted from my Medium account. Check it out for more posts like these.

Aren’t airships such a surreal method of transport? They just shouldn’t seem to work. Massive cylindrical tubes held up by nothing by lighter-than-air gas, floating through the skies.

And by massive, I mean massive.

For context, most conventional commercial planes are about 40-50 metres (131-164 feet) long. The A380, the world’s largest passenger airline, is 73 metres (240 feet).

How long was the Hindenburg? 245 metres (804 feet).

Throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s, these surreal beasts were once considered the future of transportation. But as we obviously now know, they were eventually rendered irrelevant because of aeroplanes.

Contrary to popular belief, the Hindenburg crash was not what killed the airship trend. Sure, the tragic event didn’t help, with 35 of the 97 passengers killed as the Hindenburg erupted into flames upon descent, in front of newsreel cameras. But at that point in time in 1937, airships were already falling out of fashion fast.

The main reason is that aeroplanes were finally realising their potential. With technological developments, their speed and range exploded. The DC-3, one of the most iconic planes ever, was introduced in 1936. Around the same time, Pan Am took off with Martins’ China Clipper, marking the first nonstop flight between San Francisco and Honolulu, Hawaii – a 3,840 kilometre route which was the world’s longest major route at the time (without an emergency landing field in the middle).

No matter how you spin it, the airship era was ending. Enter the era of planes.

But now, airships may be making a comeback. How? They’re much slower and clunky than aeroplanes, you may be thinking. And you’d be correct.

But there’s one application for which speed isn’t such a priority: freight.

Freight Market

The Freight market has three main categories: water (shipping), land (trucking), and air (planes). Altogether, they constitute a continuum from slow and cheap, to expensive and fast. Take a look at the following data for average freight revenue per ton mile, according to the US Bureau of Transportation Statistics:

And when you consider the amount of goods shipped by each type of transport (again, from the Bureau of Transportation Statistics) one thing stands out clearly: trucks dominate the scene.

Okay, so trucks hit the sweet spot between price and speed. But note that this is for the domestic market, not the international one. For international freight, the only main methods are air and water. Trucks aren’t present as a goldilocks alternative.

Enter airships. Airships are slower than planes, but they’re faster than ships. And they may be more expensive than shipping, but they can be cheaper than planes.

They can hence serve as the trucks of the skies, providing a goldilocks option for cargo that can be transported reasonably fast and cheap.

If you draw a parallel between the international and domestic US market, it’s not unreasonable to think that the majority of transport (both by tonnage and value) would choose airships instead.

How much disruption could this cause in economic terms? A lot. According to UNCTAD, Clarksons Research estimates that seaborne trade reached 59.5 trillion ton-miles in 2019. If airships captured just 10% of that figure, and assuming NO GROWTH of the seaborne trade market, they could capture 5.95 trillion ton-miles of the market.

At a lowball estimate of 10¢ per ton-mile, that’s $595 billion of revenue.

That’s seven times what the world’s largest shipping company by revenue, China Ocean Shipping Company, made in 2022 revenue ($84 billion).

Engineering Basics

Why are airships so suited to fulfil this sweet-spot niche in international freight? Simply put, their mechanical structure lends itself to pure, beautiful, efficiency.

Airships rely on using lighter-than-air gas for lift. They come in three main types: non-rigid, semi-rigid, and rigid.

- Non-rigid airships (commonly known as blimps) are the smallest type of airships, having a flexible envelope filled with gas. They are similar to balloons, relying only on internal pressure to maintain their shape. Hence, blimps face size scaling issues: the larger the blimp is, the harder it is to maintain its internal pressure and shape.

- Semi-rigid airships have a partial rigid structure supporting the envelope, providing greater stability and payload capacity than non-rigid designs. They can scale larger than non-rigid airships, but still eventually face scaling issues.

- Rigid airships have a solid framework to maintain the envelope’s shape. They also have gas packed in individual gas cells – large bags containing the lifting gas. Their rigid structure offers the most stability, allowing them to scale to larger sizes than the other two airship types. (Thus, they also have the highest cargo capacity among the three types.)

Hence, rigid airships are uniquely positioned to scale at large sizes to carry freight. This scalability also presents a unique advantage in freight transport.

This is because of the square-cubed law. Essentially, imagine a cube that doubles in length. Its volume increases by two cubed (8), while its surface area increases by two squared (4). Hence, its volume increases faster than its surface area.

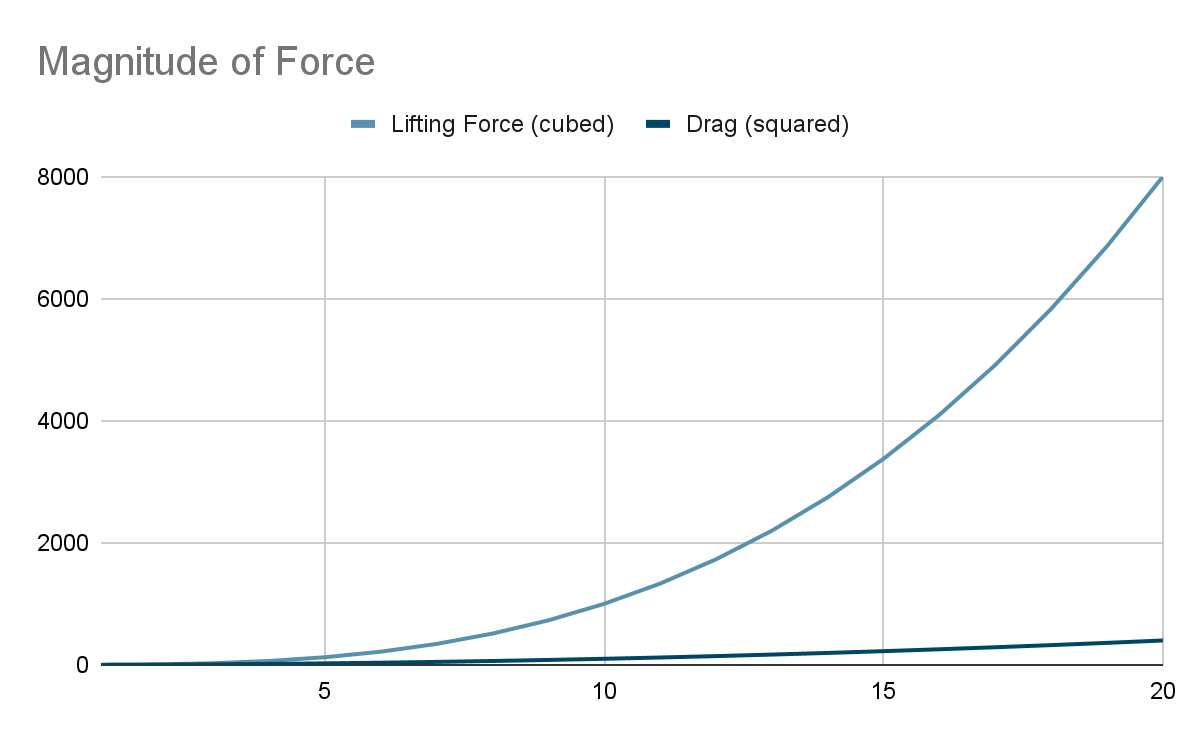

This principle also works for airships. As airships increase in size, their volume expands faster (cubed) than their cross-sectional area (squared). This is useful because lifting force is correlated with volume (cubed), and the drag force acting against their movement is correlated with cross-sectional area (squared). Hence, as airships increase in length, they become more efficient, and the payload they can carry grows disproportionately relative to the increase in length.

Lifting force is proportional to volume (which is proportional to length cubed), while drag is proportional to cross-sectional area (which is proportional to length squared).

Moreover, in rigid airships, as size increases, the proportion of mass contributed by the rigid hull decreases. This means that rigid airships grow even more efficiently than square-cubed.

This process can go on for practically forever: the larger they are, the more cargo they can carry efficiently, making them an ideal choice for international freight.

Also, airships offer unparalleled versatility in reaching diverse destinations with minimal infrastructure requirements. Other freight methods require heavy infrastructure: ships need water and ports, trucks need roads, trains need tracks and stations, planes need airports.

Airships only need a relatively flat surface for takeoff and landing: different terrains like grass, sand, ice, or even water will do.

This minimal infrastructure demand enables airships to access remote locations that may lack transport connectivity, such as rural villages in Alaska or Mongolia. Also, airships can be especially useful in disaster-stricken areas where infrastructure like roads and airports have been destroyed by natural disasters or war.

Not bad, huh? There’s more. Airships excel at transporting goods that may be incompatible with other methods due to their size, fragility, or shape. For instance, cumbersome wind turbine components can be efficiently transported via airship, avoiding the logistical challenges posed by ground transportation.

Thus, airships serve as a flexible and effective solution for international freight, balancing speed and cost-effectiveness while reaching destinations inaccessible to other modes of transport.

Issues

Of course, airships still have a long way to go before truly realising their potential as the trucks of the skies. They have multiple issues.

First, due to airships being so light and big, even a small current can cause them to be difficult to control. To combat this, engineers have experimented with putting propellers on their hulls, but the sail effect still holds.

Also, there’s issues when the cargo weight is released: without heavy weight to ground the airship down, it’ll just sail further up into the air. Some solutions (such as venting lifting gas, compressing lifting gas, and using propellers to push the airship down) have been raised, but they’re all either expensive, impractical, or infeasible with today’s technology. Hence, the most feasible method we have right now is just to replace the weight that’s being released: if you release 100 kg of cargo, mount 100 kg of wood to replace it. This is a decent short-term measure, but is extremely inconvenient on a large scale.

Also, the age-old question remains: hydrogen or helium? While hydrogen is flammable, helium is extremely expensive. Helium costs about $7.57 per cubic metre according to USGS, while hydrogen costs $0.06 to $0.12 per cubic metre according to Indexbox. In a great blog post by Eli Duorado, he calculates that it would cost almost $8 million to fill a 500-ton airship with helium, compared to slightly over $100k for hydrogen.

Also, Duorado further notes that there may be a serious issue of whether the world has enough helium for this at all. He calculates that if half of the existing ocean container market is disrupted by airships, there is demand for ~25,000 airships, which would require 26 billion m3 of helium. That’s two-thirds of the estimated 40 billion m3 of helium reserves in the entire world.

Clearly, if airships are to be adopted at a large scale, hydrogen will be essential. But as gas cells inevitably leak lifting gas over time (since both hydrogen and helium have such small molecules), it will also be essential to design foolproof ventilation systems.

Also, for many countries including the US, hydrogen is banned as a lifting gas. Before we can even consider using hydrogen in airships on a large scale, we’ll first need to get the social and political support necessary to allow it in the first place.

However, the tides are turning. The European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EUSA) allows hydrogen to be used as a lifting gas, while calls are growing for the US’ FAA to do the same.

Today, most airship companies just focus on niche markets with decently high margins, where airships are the only viable source of transport, (e.g., disaster relief zones where critical infrastructure for other transport modes has been destroyed). But as airships make their comeback, they may start competing with ships and planes for more general purpose freight functionalities.

Whatever the case is, keep a lookout for the trucks of the skies.

Leave a comment